Case Report

Volume-4 Issue-1, 2025

18F-FDG PET, New Tool for Identification of Left Atrial Structural Remodeling in Persistent Atrial Fibrillation? A Case Report

Received Date: December 06, 2024

Accepted Date: January 06, 2025

Published Date: January 09, 2025

Journal Information

Abstract

Background: 18F-FDG PET is an emerging tool for atrial glucose metabolism evaluation in the field of atrial fibrillation (AF) and its usefulness in the assessment of left atrial structural remodeling during AF is unknown.

Case Summary: patient with history of pulmonary sarcoidosis presented with symptomatic persistent AF. Cardiac sarcoidosis was suspected and 18F-FDG PET was performed during AF. Images revealed an excellent suppression of ventricular physiologic myocardial 18F-FDG uptake.However, the wall of both the left and right atrium presented a diffuse and homogeneous 18F-FDG uptake. Pericarditis, myocarditis and cardiac sarcoidosis were excluded. After pulmonary veins isolation procedure, a follow-up 18F-FDG PET/CT was scheduled after 5 months of sinus rhythm (SR) with same preparation. Images revealed a complete disappearance of 18F-FDG uptake in both atrial wall.

Discussion: Glucose metabolism evaluated by 18F-FDG PET/CT is significantly increased in AF relative to SR. This suggests either higher overall myocardial metabolism and lower myocardial efficiency or metabolic shift to glucose as substrate in AF. This case report raises the question of the place of PET scanning as an interesting potential tool in the evaluation of the atrial remodeling process in AF patients.

Key words

Keywords: Case Report, Persistent Atrial Fibrillation, Atrial structural remodelling, Atrial wall glucose metabolism, 18F-FDG Positron Emission Tomography

| During AF | After 5 months of Sinus Rhythm restore | |||||||

| SUV max | SUV mean | Bck SUV mean | TBR SUV mean | SUV max | SUV mean | Bck SUV mean | TBR SUV mean | |

| Right artrium (RA) | 5.83 | 3.44 | 1.06 | 3.25 | 1.71 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1 |

| Interatrial septum (IAS) | 4.02 | 2.66 | 1.06 | 2.51 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Left artrium (LA) | 6.08 | 3.35 | 1.17 | 2.86 | 1.71 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1 |

| Left artrium appendage (LAA) | 6.26 | 3.16 | 1.17 | 2.70 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Left ventricle (LV) | 1.91 | 0.96 | 1.4 | 0.69 | 4.65 | 1.98 | 1.16 | 1.46 |

| IA/LV ratio | 1.898 | 3.489 | NA | NA | 0.37 | 0.55 | NA | NA |

|

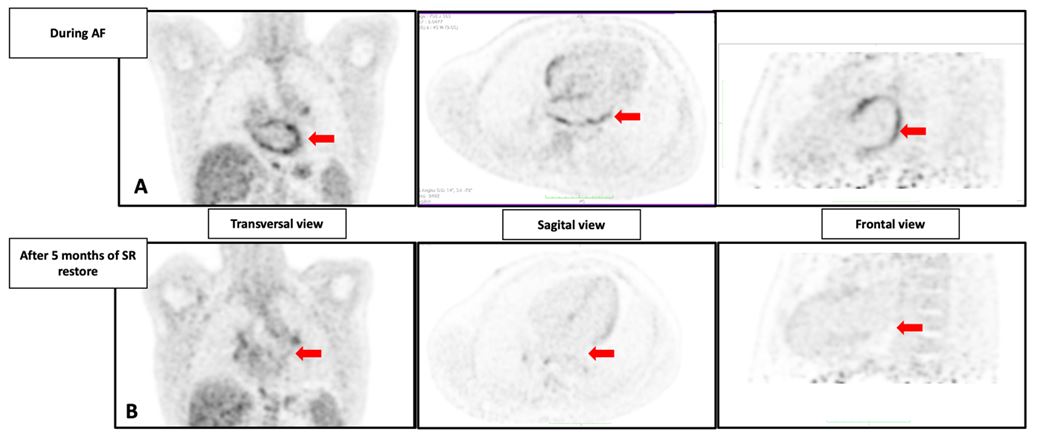

| Figure 1: Two Dimension 18F-FDG uptake performed in patient during Atrial Fibrillation (AF) and 5 months after sinus rhythm (SR) restoration: PET imaging in transversal, sagittal, frontal view (A) and A-P view (B) shows a decrease of the 18F-FDG uptake after 5 months of SR. Quantification of Left Atrial 18F- FDG uptake using MIM software. Exams and analysis performed with same contrast scale, same patient preparation, same image acquisition, same image preprocessing. The arrows points toward specific heart structures.LA: Left Atrium. |

Established Facts and Novel Insights

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is characterized by irregular high-frequency excitation and contractions that affect atrial wall energy demands, resulting in metabolic stress.

This metabolic imbalance increases glucose uptake and is associated with the development of left atrial remodeling, which predicts AF persistence.

In this case we observed that glucose metabolism evaluated by 18F-FDG PET is significantly increased in AF relative to sinus rhythm. This suggests either higher overall myocardial metabolism and lower myocardial efficiency or metabolic shift to glucose as substrate in AF.

This case report raises the question of the place of PET scanning as an interesting potential tool in the evaluation of the atrial remodeling process in AF patients.

Introduction

Atrial Fibrillation (AF) is characterized by irregular high-frequency excitation and contraction that affect atrial energy demands, change the balance between metabolic demand and supply and modify the cellular glucose metabolism. This metabolic change during AF is associated with the development of Left Atrial (LA) remodeling. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET) is an emerging tool for atrial glucose metabolism evaluation in the field of AF and its usefulness in the assessment of left atrial structural remodeling during AF is unknown [1-3].

Case

A 45-year-old man with pulmonary sarcoidosis presented with symptomatic persistent AF. He had no history of smoking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease (CAD), or family history of premature CAD or stroke. There was no recent severe illness or travel outside Europe.

Cardiac sarcoidosis was suspected, and an 18F-FDG PET was performed prior to pharmacological cardioversion, following European and American nuclear medicine guidelines. The patient received a high-fat, low-carbohydrate meal before the PET, followed by 12 hours of fasting. The images showed excellent suppression of ventricular myocardial 18F-FDG uptake (SUVmean LV wall 0.96, LV cavity 1.40), indicating proper preparation. No focal 18F-FDG uptake was observed in the ventricular wall, excluding active cardiac sarcoidosis. However, diffuse 18F-FDG uptake was seen in both atrial wall (right atrium SUVmean 3.44, interatrial septum 2.66, left atrium 3.35). See figure 1 and table 1.

Examinations including laboratory results, Doppler echocardiography, cardiac MRI, and rheumatology consultation ruled out pericarditis, myocarditis, and cardiac sarcoidosis. No anti-inflammatory treatment was prescribed. The patient underwent successful pulmonary vein isolation and had no recurrence of AF during follow-up.

A follow-up 18F-FDG PET after 5 months of sinus rhythm, with the same dietary preparation, showed complete resolution of atrial wall 18F-FDG uptake (SUVmean 1.09). Mild 18F-FDG uptake was noted in the left ventricular wall (SUVmean of 1.98 vs SUVmean in the LV cavity of 1.16), indicating suboptimal myocardial suppression (see figure 1). The atrial SUVmean was equal to background levels.

Discussion

This case describes a significant change in FDG uptake in the atrial wall in the same patient following cardioversion for atrial fibrillation (AF). We demonstrated that 18F-FDG PET, performed just before pharmacological cardioversion for persistent AF, revealed markedly increased tracer uptake in the atrial wall compared to the ventricular wall. A follow-up 18F-FDG PET scan, performed under similar conditions after 5 months of sinus rhythm, showed that this metabolic activity in the atrial wall had disappeared.

Atrial remodeling in AF is complex, involving several mechanisms such as inflammation, oxidative stress, mechanical stretching, and ischemia [4,5]. Changes in cardiac metabolism in the atrial wall during AF reflect a shift from fatty acid oxidation to glucose uptake. The intense FDG uptake seen in the initial PET scan may highlight this metabolic shift, as well as the relative ischemic processes in AF described in the literature [3]. Previous studies have shown that the energy metabolism of atrial cardiomyocytes during AF leads to metabolic stress, which is associated with various cellular changes, including a metabolic shift to a more fetal phenotype and activation of AMP-activated protein kinase [4,5]. These alterations increase the expression of glucose transporters and enhance their trafficking into the sarcolemma, thus promoting glucose uptake [4].

In this case, the 18F-FDG PET imaging preparation was similar to that used for imaging infections or inflammatory diseases. Previous research has shown that cells involved in infection and inflammation, particularly neutrophils and the monocyte/macrophage family, can express high levels of glucose transporters and exhibit increased hexokinase activity. Both experimental (histological analysis of atrial biopsies) and clinical data indicate that inflammation plays a role in atrial remodeling. The intense FDG uptake observed in the initial PET scan could thus reflect these inflammatory processes [6]. However, the absence of inflammation markers in blood tests and a normal cardiac MRI makes this explanation less likely. Atrial biopsies or Gallium-68-labeled fibroblast activation protein inhibitor PET scans could provide further insight into this issue. Besides providing further insights into the pathophysiology of AF, this case report demonstrates the interest of FDG PET for high-quality atrial imaging in vivo. This technique may be comparable to LGE cMR and other imaging techniques, potentially providing clinical applications in evaluating atrial remodeling prior to catheter ablation procedure with a noninvasive method for quantifying and localizing LA remodeling. This suggests that studying atrial metabolism hold promises for guiding physicians and deepening our understanding of atrial remodeling during persistent AF since FDG-PET uptake could serve as an indication of preserved atrial myocyte function, thereby demonstrating the absence of atrial fibrosis. Further research should investigate the potential utility of this non-invasive imaging technology in clinical practice with largest population in order to confirm the correlation between 18F-FDG-PET uptake and AF structural remodeling or atrial cardiomyopathy, to guide AF ablation strategies and predict the outcomes of AF ablation procedures.

Conclusion

We observed in this case that glucose metabolism evaluated by 18F-FDG PET is significantly increased in AF relative to SR. This suggests either higher overall myocardial metabolism and lower myocardial efficiency or metabolic shift to glucose as substrate in AF. This case report raises the question of the place of PET scanning as an interesting potential tool in the evaluation of the atrial remodeling process in AF patients. This requires future ambitious prospective studies.

Ethical Approval Details

IRB 2018/17OCT/389. TRIATLON; Eudract reference 2019-001813-17A

Funding Information - Conflict of Interest

None Declared

Informed Consent

NA

References

- Xie B, Chen BX, Nanna M, Wu JY, Zhou Y, et al. (2021) 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging in atrial fibrillation: a pilot prospective study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 23: 102-12.

- Hesse M, Marchandise S, Gerber B, Roelants V (2023) Cardiac atrial metabolism quantitative assessment with analog and digital time of flight-PET/computed tomography. Nucl Med Commun. 44: 646-52.

- Marchandise S, Roelants V, Raoult T, Garnir Q, Scavée C, et al. (2024) Left Atrial Glucose Metabolism Evaluation by 18F-FDG-PET in Persistent Atrial Fibrillation and in Sinus Rhythm. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 9: 459-71.

- Harada M, Melka J, Sobue Y, Nattel S (2017) Metabolic Considerations in Atrial Fibrillation - Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Opportunities. Circ J. 81: 1749-57.

- Nattel S, Heijman J, Zhou L, Dobrev D (2020) Molecular Basis of Atrial Fibrillation Pathophysiology and Therapy: A Translational Perspective. Circ Res. 127: 51-72.

- Aghayev A (2022) Is glucose metabolism in the atria in patients with atrial fibrillation due to inflammation or remodeling? J Nucl Cardiol. 29: 2837-8.

Article Information

Case Report

Received Date: December 06, 2024

Accepted Date: January 06, 2025

Published Date: January 09, 2025

18F-FDG PET, New Tool for Identification of Left Atrial Structural Remodeling in Persistent Atrial Fibrillation? A Case Report

Volume 4 | Issue 1

Citation

Sebastien Marchandise MD, PhD, Véronique Roelants MD, PhD, Jean-Benoit le Polain de Waroux MD, PhD, Bernhard L. Gerber MD, PhD FESC FAHA FACC (2025) 18F-FDG PET, New Tool for Identification of Left Atrial Structural Remodeling in Persistent Atrial Fibrillation? A Case Report. Eur J Case Rep 4: 1-5

Copyright

©2025 Sebastien Marchandise MD. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

doi: ejcr.2025.4.101